Que signifierait imaginer la psychanalyse autrement ? Ce chapitre s’enquiert de ce que la psychanalyse pourrait avoir à gagner d’une confrontation intellectuelle et éthique sérieuse avec les enjeux épistémiques et ontologiques de la tradition islamique. Je procède épisodiquement et géohistoriquement, avec une référence spécifique au monde arabe et à la France. En premier lieu, j’étudie certains des débats conceptuels autour de la psychanalyse et de l’islam au moyen d’une brève discussion des travaux de Julia Kristeva et de Fethi Benslama. Je récapitule ensuite la littérature sur la psychanalyse et la question religieuse, y compris des travaux récents qui repensent ensemble la psychanalyse et l’islam, non pas comme un « problème », mais comme une rencontre créative au sein d’une confrontation éthique. En troisième lieu, j’en viens à présenter le travail de Sami-Ali dont le recours à la métaphysique islamique et à la théologie apophatique a permis de repenser de manière critique le rôle de l’imaginaire, les mécanismes de projection, et l’épistémologie du non-savoir dans le travail de l’inconscient. Pour finir, je conclus par une critique de l’idée de travail de la culture en tant que travail de laïcité. Plutôt que d’imaginer la psychanalyse comme une discipline séculière sur le plan normatif, cette approche achemine les concepts philosophiques et théologiques islamiques dans le giron de la tradition psychanalytique.

Category: Articles

The Work of Illness in the Aftermath of a ‘Surpassing Disaster’: Medical Humanities in the Middle East and North Africa

How might Middle East studies transform the Medical Humanities, broadly conceived? Drawing inspiration from Georges Canguilhem’s epistemology of medicine and Frantz Fanon’s theorization of the intersection of psychiatry and medicine, I argue that rather than an approach that simply adds the Middle East to purportedly epistemologically secure notions of medicine and psychiatry, we might, alongside these thinkers, query the stability of such practices as uniform Western formations.

Inwardness: Comparative Religious Philosophy in Modern Egypt

This article centers the Islamic philosopher ʿUthman Amin in order to explore the intellectual exchange

between Muslim and Christian scholars in twentieth-century Egypt. Specifically, I look at inwardness, intellectual dialogue, and interreligious friendships in a field that has traditionally been dominated by scholarship on the relationship between Islam and politics or Islam and the law. I elucidate Amin’s philosophy of inwardness and its attendant virtues of seclusion, spiritual contemplation, and the jihad of the self—paying particular attention to reading as an illuminative embodied practice—through the lens of an Islamic discursive tradition. How might we understand the concept of an Islamic discursive tradition, as a philosophy of reasoned and embodied religion, within the context of such interreligious encounters? Amin, I argue, was engaged in an experimentum mentis in which inwardness provided an angle of lucidity from which Islam and Christianity could gaze upon one another. In so doing, I demonstrate the heuristic value of theorizations of tradition by Alasdair MacIntyre and Talal Asad to studies of interreligious encounter and scholarly exchange.

Colonialism and Postcolonial Theory: Race, Culture, and Religion in Psychosocial Studies

“If,” as Robert Young notes, “‘so-called post-structuralism’ is the product of a single historical moment, then that moment is probably not May 1968 but rather the Algerian War of Independence.” We might also argue that the most radical reconfiguration of psychosocial studies likewise occurred under the duress of that War. The rethinking of relations between Self and Other spawned by the colonial encounter, first in the Antilles and later most dramatically in Algeria, led Frantz Fanon (1925–1961) to successively theorize the psycho-existential implications of the juxtaposition of the races and the psychopolitics of colonialism. Taking Fanon as its pivot, this chapter looks backwards and forwards from the 1950s, proceeding episodically and geohistorically in order to understand the interconnections between psychosocial studies, colonialism, and postcolonial theory. First, I explore the figure of the non-European in psychoanalysis and ethnopsychiatry. Second, I turn to the work of Frantz Fanon and the scholars who have written in his shadow, investigating the fictions and antinomies of (post)colonial constructions of race. I then problematize the status of ‘culture’ and ‘religion’ by identifying a central aporia within psychosocial studies, namely the question of religion and the secular. How might rethinking the secular open up both the archive of psychosocial studies and the question of ethics? Finally, I end with a discussion of our present moment, touching on decolonial works that seek to interrogate whiteness. Rather than a comprehensive and exhaustive review of the literature, this chapter engages texts that address the interstitial space between psychology and politics, metropole and colony, with an emphasis upon ethics as it relates to the theory and clinical practice of psychosocial studies.

Rethinking Arab Intellectual History: Epistemology, Historicism, Secularism

Arab intellectual history has been experiencing a resurgence of late, positioned as it is between the ascendancy of global intellectual history and the continued resilience of area studies. Such a precipitous conjuncture has led to a proliferation of Arab intellectual histories that belie the Orientalist fallacy of the region as a “no idea producing area,” as once infelicitously described by Charles F. Gallagher. And yet, the task of scholars of the Arab world is surely more complex than merely adding intellectuals and writers who have heretofore been ignored to the canon of intellectual history. One might argue that the field of intellectual history has yet to grapple fully with its geo-historical and geo-political location, mired as it is in a parochialism that has assumed the singular centrality of Western European intellectual traditions in the formation of its canon. Within these intellectual formations, the non-West often makes its appearance only as an afterthought—producing exemplars but rarely epistemologies. This is evidenced in citational practices in which theoretical production is presumed to be European, while sites like Morocco, Egypt, and Syria can only inflect the empirical trajectories of intellectual movements presumed to have already taken place in the West. Given this framing (how), one might ask, can Arab intellectual history shift the contours of debates within intellectual history itself?

History and the Lesser Death

What is the role of ethics within the writing of history? And how might our ethics be connected to the psychic stakes we hold in our objects of study? As historians, what is our responsibility to the dead in our present historical moment of danger, what Sigmund Freud termed “the times of war and death”? In cultivating an ethics of listening to, and learning to speak with, the dead, how can we attend to the gravitas of this encounter, in which we are inherently implicated, both consciously and unconsciously?

Psychoanalysis and the Imaginary: Translating Freud in Postcolonial Egypt

This article imagines psychoanalysis geopolitically by way of an exploratory foray into the oeuvre of Sami-Ali, the Arabic translator of Sigmund Freud’s Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, author of a large body of original psychoanalytic writings, and translator of the poetry of Sufi masters. Taken together, his writings enable a critical rethinking of the role of the imaginary, the mechanisms of projection, and the epistemology of non-knowledge in the workings of the unconscious. Significantly, such a rethinking of key psychoanalytic concepts drew upon the Sufi metaphysics of the imagination of Ibn ʿArabi. Yet such theoretical work cannot be understood outside of its wider clinical context and the conditions of (im)possibility that structure psychoanalysis within the postcolony. Reconstituting Sami-Ali’s early theoretical writings alongside his work with the long-forgotten figures he observed, incarcerated female prostitutes in 1950s Cairo, I argue that his clinical encounters constituted the ground of his theorization of the imaginary within the embodied subject. Attending to the work of translation inherent within psychoanalytic practice – whether from Sigmund Freud’s own German writings into French or Arabic, or from clinical practice into theoretical discourse – helps us conceptualize psychoanalysis as taking place otherwise at the intersection of multiple epistemological and ethical traditions.

Introduction: Psychoanalysis and the Middle East (with Sara Pursley & Caroline McKusick)

This special issue stages an encounter between psychoanalysis and the Middle East. Taking seriously the possibility of an alchemical transformation of psychoanalytic thought through its encounter with the Middle East and with Islam, chapters reopen the psychoanalytic canon to consider key concepts through unexpected interlocutors, religious traditions, and intellectual formations. This includes bringing medieval Islamic philosophical concepts of the Cloud to bear on conceptions of causality and après coup; and thinking from the point of view of the Last Judgment in dialogue with the therapeutic work of a Moroccan imam and the Lacanian analyst Fouad Benchekroun. Authors also recover lesser known histories of psychoanalytic theory: in the work of Egyptian psychoanalytic theorist Sami-Ali, who developed a distinctly expansive theory of the imaginary influenced by Islamic apophatic theology and his own clinical work; and in Iraqi sociologist ʿAli al-Wardi’s critical reevaluation of the unconscious, via the Islamic revolutionary tradition, as a source of the miraculous. Moving to the contemporary era, chapters tackle the various uses of psychoanalysis in ‘dialogue initiatives’ that delegitimize Palestinians’ use of violence in Palestine/Israel; and in efforts to ‘lay on the couch’ the figure of the jihadi in contemporary France in the service of a secular modernizing project. Engaging critical theory, history, anthropology, literary studies, and Islamic studies, this special issue will be of interest to all those concerned with psychoanalysis in relation to a geopolitical elsewhere.

What is the Future of Psychoanalysis in the Academy?

The death of psychoanalysis has been foretold countless times, and yet, like the unresolvable excess of mourning, it persists.

Translation, Tradition, and the Ethical Turn—A Reply to Bardawil and Allan

In the “Task of the Translator,” Walter Benjamin observes that “a translation issues from the original—not so much from its life as from its afterlife.” The Arabic Freud, as both Michael Allan and Fadi Bardawil remark, models the ethos and practice of translation through its method. Here, the work of translation is “not mired in a question of translational directionality,” nor is it understood in terms of “causality, fidelity, and adaptation,” as Michael Allan astutely notes, but rather translation is imagined as a constitutive afterlife. Within this shifted terrain, away from “margin and center, and toward the site of reception and rebirth,” he continues, Freud emerges “as a site and occasion for understanding the poetics of reception.” Allan pushes me further to think about the vector from adaptation back to source, about the implications that the Arabic Freud had on the German Freud. Indeed, as Benjamin continues, “in its afterlife—which could not be called that if it were not a transformation and renewal of something living—the original undergoes a change.”

The Arabic Freud: The Unconscious and the Modern Subject

This essay considers how Freud traveled in postwar Egypt through an exploration of the work of Yusuf Murad, the founder of a school of thought within the psychological and human sciences, and provides a close study of the journal he co-edited, Majallat ʿIlm al-Nafs. Translating and blending key concepts from psychoanalysis and psychology with classical Islamic concepts, Murad put forth a dynamic and dialectical approach to selfhood that emphasized the unity of the self, while often insisting on an epistemological and ethical heterogeneity from European psychoanalytic thought, embodied in a rejection of the dissolution of the self and of the death drive. In stark contrast to the so-called “tale of mutual ignorance” between Islam and psychoanalysis, the essay traces a tale of historical interactions, hybridizations, and interconnected webs of knowledge production between the Arab world and Europe. Moving away from binary models of selfhood as either modern or traditional, Western or non-Western, it examines the points of condensation and divergence, and the epistemological resonances that psychoanalytic writings had in postwar Egypt. The coproduction of psychoanalytic knowledge across Arab and European knowledge formations definitively demonstrates the outmoded nature of historical models that presuppose originals and bad copies of the global modern subject—herself so constitutively defined by the presence of the unconscious.

History Without Documents: The Vexed Archives of Decolonization in the Middle East

In Sonallah Ibrahim’s 1981 novel The Committee, an unnamed protagonist is tasked with writing a report on the greatest “Arab luminary.” After obtaining access to the archives of a national daily newspaper through a personal recommendation, the narrator receives a much-sought-after file and recounts: “I opened the folder, my fingers trembling from excitement. It revealed a white sheet of paper with a date from the early ’50s at the top and nothing else. I turned it over and saw a similar sheet of paper. Quickly, I examined the sheets of paper in the file and saw that they all lacked everything but a date.” Jotting down the dates listed, the protagonist then cross-references them with other, more publicly available information in an attempt to reconstruct a narrative of events—piecing together what an Egyptian historian once referred to as a “history without documents.”

History Without Documents (Arabic)

في رواية صنع الله إبراهيم «اللجنة» (1981)، كُلِّف البطل غيرُ المُسمَّى بكتابة تقرير حول “النجم العربي” الأعظم، بعد تمكنه من الوصول إلى أرشيفات صحيفة وطنية يومية من خلال توصية شخصية، وبذل الراوي قصارى جهده؛ فيروي قائلاً: “فتحت الملف؛ فارتعشت أصابعي من الإثارة. أظهر (الملف) ورقة بيضاء مع تاريخ من أوائل الخمسينيات في أعلى الصفحة ولا شيء آخر، قلَّبتُها ورأيت ورقة مشابهة، بسرعة تفحصت الأوراق الموجودة في الملف ووجدت أنها تفتقر إلى كل شيء ما عدا التاريخ”. وبتدوين التواريخ، قام البطل بإحالتها إلى معلومات أخرى متاحة أكثر للجمهور في محاولة لإعادة بناء سردية للأحداث -لتجميع ما وصفه مؤرخ مصري ذات مرة بـ”تاريخ بلا وثائق”.

تاريخ بلا وثائق”.

يوضح مثال إبراهيم الأدبي معنيين لعبارة “تاريخ بلا وثائق”، أحدهما يشير إلى ما يسميه أشيل مبيمبي (Achille Mbembe) بـ”الآكل الزمني” (chronophagy) للدولة، أي الطريقة التي تَبَدد بها الماضي إما من خلال التدمير المادي للأرشيفات أو عرض تاريخ منقى من الخصومات ومُتجسِّد في حسابات تذكارية فارغة. المعنى الثاني يشير إلى التاريخ الذي قد نسعى إلى إعادة بنائه بسبب انعدام الوصول إلى مثل هذه الوثائق رغم ذلك. وهكذا، فإن الأرشيف يعمل بوصفه “تأسيسًا تخيليًّا” يسعى إلى إعادة تجميع ودفن أثر الموروث الذي يكون دائمًا غيرَ مكتملٍ، ولا سبيل إلى معرفته طوال الوقت، وجزئيًّا على الأقل، عرضًا لرغباتنا الخاصة على الدوام.

Youth as Peril and Promise: The Emergence of Adolescent Psychology in Postwar Egypt

A public discourse of “youth crisis” emerged in 1930s Egypt, partly as a response to the widespread student demonstrations of 1935 and 1936 that ushered in the figure of youth as an insurgent subject of politics. The fear of youth as unbridled political and sexual subjects foreshadowed the emergence of a discourse of adolescent psychology. By the mid-1940s, “adolescence” had been transformed into a discrete category of analysis within the newly consolidated disciplinary space of psychology and was reconfigured as a psychological stage of social adjustment, sexual repression, and existential anomie. Adolescence—perceived as both a collective temporality and a depoliticized individual interiority—became a volatile stage linked to a psychoanalytic notion of sexuality as libidinal raw energy, displacing other collective temporalities and geographies. New discursive formations, for example, of a psychology centered on unconscious sexual impulses and a cavernous interiority, and new social types, such as the “juvenile delinquent,” coalesced around the figure of adolescence in postwar Egypt.

Youth as Peril and Promise (Arabic)

نشأ خطاب عام حول “أزمة الشباب” فى مصر فى الثلاثينيات من القرن الماضى جزئيًا بوصفه رد فعل للمظاهرات الطلابية واسعة النطاق فى عامى ١٩٣٥ و ١٩٣٦ التى أرهصت بظهور صورة الشباب بوصفهم ذواتًا سياسية متمردة. وكان الخوف من الشباب بوصفهم ذواتًا سياسية وجنسية جامحة إيذانًا بنشوء خطاب حول سيكولوجية المراهق. وبحلول منتصف الأربعينيات، تحولت ” المراهقة ” إلى مقولة تحليلية متميزة داخل الحيز التخصصى المؤسس حديثًا لعلم النفس وأعيد تشكيلها بوصفها مرحلة نفسية للضبط الاجتماعى والكبت الجنسى والتفسخ الوجودى. جماعية وجوانية وأصبحت المراهقة المدركة بوصفها زمانية فردية غير مسيّسة -مرحلة تتسم بالتقلب وعدم الاستقرار وترتبط بفكرة الجنسانية فى التحليل النفسى بوصفها طاقة خام ليبيدية، لتحل محل زمانيات جغرافيات جماعية أخرى. تلاحمت إذن تشكيلات خطابية جديدة، على سبيل المثال تلك الخاصة بعلم نفس متمحور حول الدوافع الجنسية اللاواعية والجوانية عميقة الغور، مع أنماط اجتماعية جديدة، مثل الحدث الجانح حول صورة المراهقة فى مصر ما بعد الحرب.

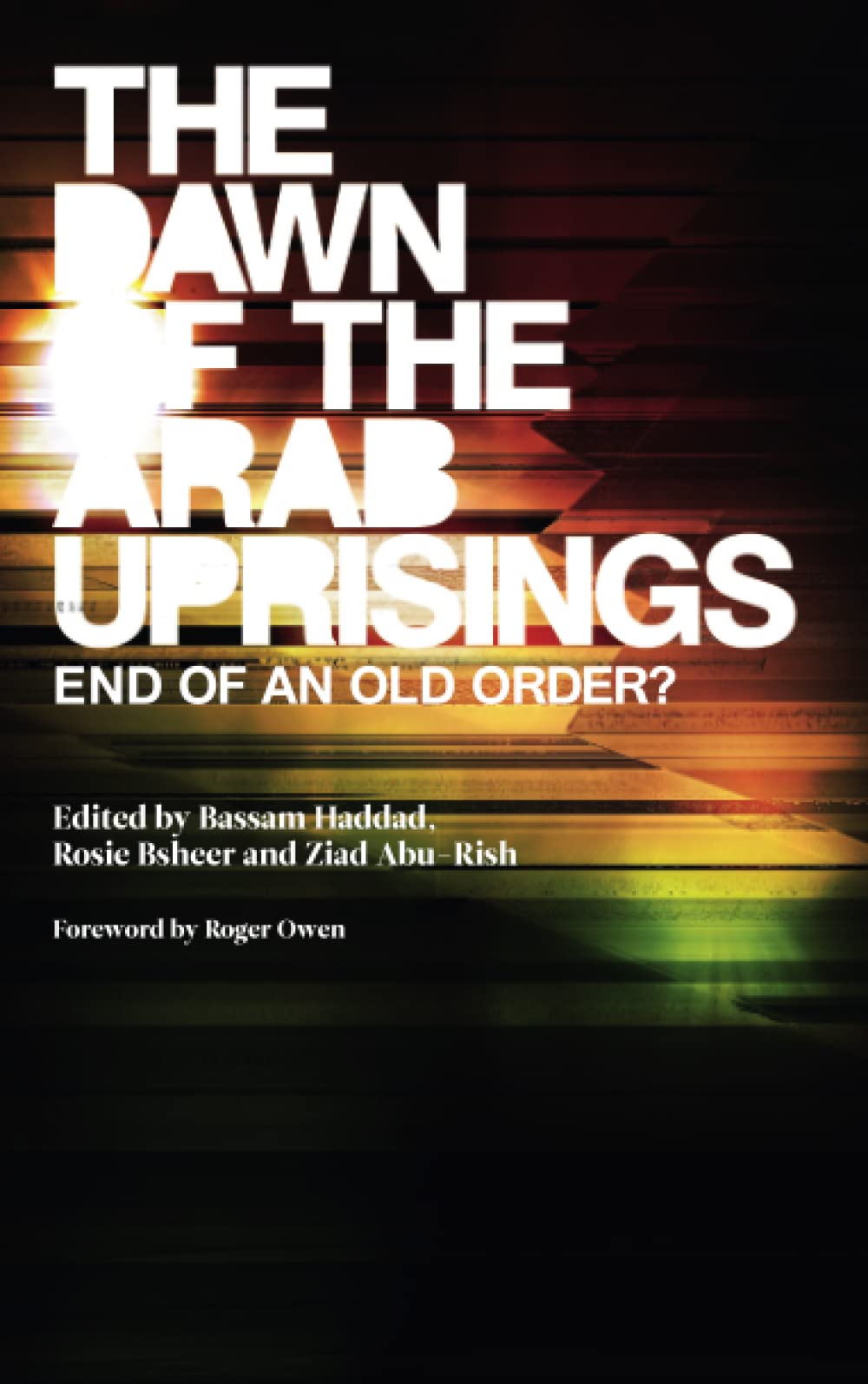

Egypt’s Three Revolutions: The Force of History behind the Popular Uprising

While an understanding of the process of privatization, economic marginalization, consumerism, and structural adjustment that we refer to as “neo-liberalism” is crucial to understanding the contemporary unfolding of events, particularly in terms of the existence of vast economic inequalities and the impoverishment of the demographic masses, a focus on neo-liberalism alone fails to address the question of the historical relationship in Egypt between ruler and ruled. What would a longer-term historical perspective, a deeper structural view of the events in Egypt look like? Focusing on popular protest and mobilization in Egypt’s 1919, 1952, and 2011 revolutions, I focus on the internal dynamics of, and discontinuities between, each of these revolutions, characterizing them as nationalist, passive, and popular, respectively.

Artistic Sovereignty in the Shadow of Post-Socialism: Egypt’s 20th Annual Youth Salon

While questions of creative sovereignty (hurriyat al-ibda‛) tend to loom large in Egyptian academic writings, the artistic trajectory of the annual juried competition known as the Youth Salon has been marked, historically, by structural inertia. Established in 1989 by the Ministry of Culture, the exhibition was meant to encourage a new generation of Egyptian artists and increase their international visibility. Jessica Winegar has explored the Salon as a “tournament of values” that is part and parcel of struggles surrounding the “shared ideal of the patron state.” Indeed, if the space of the exhibition is understood, as Boris Groys argues, as the “symbolic property of the public,” then the debates surrounding the 2009 Salon illuminate the contested nature of artistic and curatorial sovereignty in the shadow of the legacy of state socialism and a purportedly democratic mass culture of artistic consumption and production. An exploration of the controversies that erupted around the selections of the jury committee, the curatorial strategies employed in the exhibit, and the political reverberations of specific aesthetic choices, can elucidate the ways in which artistic and curatorial sovereignty can be forged in a range of historical circumstances—postcolonial, postsocialist, and beyond.

20th Annual Salon El Shabab: Youth, Art, and Controversy

Although the discussion surrounding the official jury selections of the 20th annual Salon El Shabab was expected to be tense, no one could have anticipated the heated nature of the debate surrounding the aesthetic choices of the committee. Replete with shouting matches, melodramatic walk-outs, and angry and crest-fallen artists, the discussion was indeed something to behold. As three of the members of the Salon jury committee (Bassam El Baroni, Hassan Khan, and Wael Shawky) sat alongside Mohammed Tala’at (the director of the Ministry of Culture’s Palace of Arts, Qasr el Funun), awaiting the arrival of the head of the jury committee (Ahmed Shiha) and the head of the Fine Arts Sector in the Egyptian Ministry of Culture (Mohsen Sha’alan) to introduce the panel, the audience grew increasingly apprehensive. Finally removing the remaining name placards, Tala’at introduced the wayward jury members to an audience eagerly awaiting an explanation of the narrow choice of slightly over 100 artists from a pool of over 1100, a first time occurrence in the history of the Salon. The stakes were clearly high — selection in the salon is coveted among young artists as an official point of entry for an artistic career, and representations of the question of youth in the mainstream media (with ubiquitous discussions of a “youth crisis”) mark the way in which Egyptian society views its own place in the art world and questions of its postcolonial futurity.

20th Annual Salon El Shabab: Youth, Art, and Controversy (Arabic)

كان احتدام النقاش حول اختيارات لجنة التحكيم الرسمية بصالون الشباب العشرين أمرا متوقعا، لكن أحدا لم يكن ليتنبأ بمدى اشتعال الجدل حول الاختيارات الفنية للّجنة. كانت المناقشة، التي حفلت بمباريات الصياح والانسحابات الميلودرامية والفنانين الغاضبين المحبطين، جديرة بالمشاهدة. ففي حين جلس ثلاثة من أعضاء لجنة تحكيم الصالون (بسام الباروني وحسن خان ووائل شوقي) بجوار محمد طلعت (مدير قصر الفنون التابع لوزارة الثقافة) في انتظار وصول رئيس اللجنة (أحمد شيحة) ورئيس قطاع الفنون التشكيلية بوزارة الثقافة المصرية (محسن شعلان) لبدء الندوة، تصاعد توتر الحضور. وأخيرا قام طلعت، بعدما أزاح اللافتات التي تحمل باقي الأسماء، بتقديم أعضاء اللجنة المتمردين إلى جمهور ينتظر بفراغ الصبر تفسيرا لاختيار 100 فنان فحسب من بين 1100 من المتقدمين، وهي سابقة في تاريخ الصالون. من الواضح أن المخاطرة كانت كبيرة- فالفنانون الشباب يتشبثون بأمل الاشتراك في الصالون بوصفه نقطة البداية الرسمية لمسيرتهم الفنية، كما أن أسلوب تصوير الإعلام السائد لقضية الشباب (والمناقشات المتواصلة حول “أزمة الشباب”) يتحكم في نظرة المجتمع المصري لمكانه في عالم الفن والتساؤلات المتعلقة بمستقبله في مرحلة ما بعد الاستعمار.

The Body Doubled: Artistic Strategies, the Body, and Public Space

Indicated by Signs was an international project jointly formed by curators based in Egypt, Germany, Lebanon and Morocco and presented in a series of exhibitions of newly commissioned and existing work, presentations, workshops, residencies and a publication.

Dense Objects and Sentient Viewings: Contemporary Art Criticism and the Middle East

An outline of recent trends in contemporary artistic production in and about the Middle East, which critically explores the prevalence of binary understandings of the region as trapped between local ethno-nationalisms and global neo-liberalisms, or between politics and aesthetics.

Dense Objects and Sentient Viewings (Turkish)

An outline of recent trends in contemporary artistic production in and about the Middle East, which critically explores the prevalence of binary understandings of the region as trapped between local ethno-nationalisms and global neo-liberalisms, or between politics and aesthetics.

Reproducing the Family: Biopolitics in Twentieth-Century Egypt

This chapter provides an intellectual history of twentieth-century biopolitics in Egypt. Tracing the origins of population discourse to the late 1930s, it explores how population debates revolved around the neo-Malthusian reduction of the birth rate and the improvement of the characteristics of the population through eugenics. It then tracks the shifting nature of population policy across two distinct biopolitical regimes-one, from the 1930s to the 1960s, centered on the state as arbiter of social welfare, and a second, beginning in the 1970s, centered on socioeconomic development and a more direct promotion of family planning through media efforts. Throughout the twentieth century, orthodox Islamic religious discourses were complementary rather than antithetical to these modern biopolitical regimes. The chapter pays particular attention to the relationships among gender, reproduction, and demographic mandates in modern Egypt, arguing that the regulation of women has functioned as the fulcrum of population policies.

Barren Land and Fecund Bodies: The Emergence of Population Discourse in Interwar Egypt

The constitution of population as both an object of knowledge requiring observation and management through “numbers, statistics, material phenomena,” and as a social problem to be modified for the progress of the human race, I argue, took shape in Egypt in the interwar period. However, the parameters within which the problem of population were discussed during this time period were far broader than that of contemporary discussions, entailing fields of knowledge as varied as medicine, geography, and sociology, in part due to the embryonic nature of specialized fields of expertise such as demography, vital statistics and eugenics. It is this convergence of overlapping fields of knowledge—which took the calculus of life and death, of the fecundity of lands and bodies into consideration and which concerned itself with the scientific reform of society—that marks population politics at this time.

Cairo as Capital of Socialist Revolution?

This chapter evokes two very different spectacles of modernity as illustrations of two contrasting spatial modes of regulation: a social-welfare mode of regulation for the period spanning the 1930s to the 1960s, and a neoliberal mode of regulation for the period after economic liberalization (Infitah), roughly beginning in the late 1970s. In what follows, I contend that the land-reclamation schemes inaugurated under Nasser (such as Tahrir Province), on the one hand, and the new desert settlements and Greater Cairo schemes promoted after Infitah, on the other, were each indicative of spatial practices enmeshed within the reproduction of a particular ‘mode of regulation.’

Science: Medicalization and the Female Body

This entry explores the emergence of scientific discourses on women and gender in Islamic cultures in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries through the transformation of the notion of science from “useful arts” to modern forms of scientific knowledge and practices.

Schooled Mothers and Structured Play: Child-Rearing in Turn of the Century Egypt

This essay attempts to explore some of the conjunctures and disjunctures between European colonial and metropolitan discourses and indigenous modernizing and nationalist discourses on women and mothering in turn-of-the-century Egypt. Tracing the proliferation of debates on motherhood and proper child rearing through a number of scientific-literary and religious journals, I will attempt to elaborate the changing conception of the “good mother” and proper mothering as situated within the contemporaneous dis-courses of domesticity.1I will be analyzing what Dipesh Chakrabarty has recently referred to as “public narratives of the nature of social life in the family.” Such narratives crystallized into a normative and didactic discourse that helped to re-create and redefine the parameters of what was considered ideal in conceptions of motherhood, child rearing, and domesticity within a colonial context.